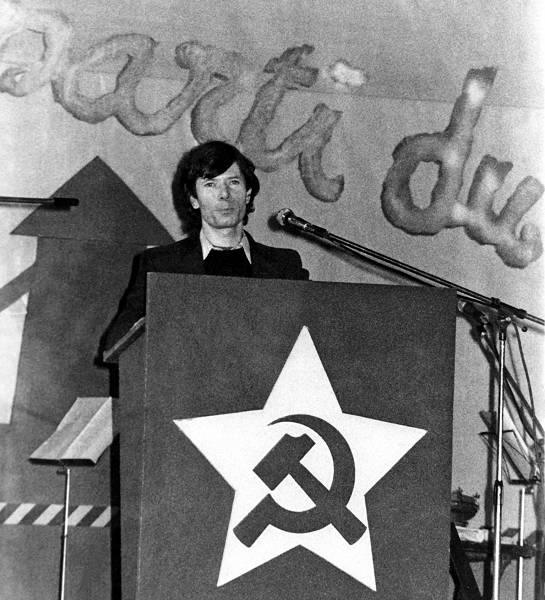

The People’s Union (VU), a Flemish nationalist party, was formed in 1954 to promote the Flemish language. The VU later broadened its scope and became a big tent organisation, successfully attracting voters from both the left, the centre and the right. The VU contributed to the growing attention given to the Flemish question in the 1970s, at a time when the established parties split into Vallonian and Flanderian branches. Eventually the VU also split, when a more radical faction, who did not accept the compromise on the federal solution, left. In the 1978 election, an alliance of two small radically nationalist parties was formed, which in 1979 was turned into a new political party: Vlaams Blok (VB).

The Vlaams Blok did not make much noise in its early years, being active mostly in the city of Antwerp, and with total focus on the issue of independence for Flanders. In the mid 1980s, the party’s attention gradually shifted towards anti-immigration messages. In 1987 a youth organization was formed by among others future party leader Filip Dewinter. The big break came in the EP elections in 1989, followed by a strong result in the Belgian elections in 1991, which became known as “Black Sunday” in Belgium. VB then continued to grow, increasing their share of the votes in every election from 1981 to 2007.

VB has a long history of extremism and occasionally even anti-semitism. Its first party leader, Karel Dillen, elected to the post for life in 1981 (he eventually resigned in 1996, continuing as an MEP until 2004) translated a Holocaust denial book in the 1950s. In the early 2000s, vice-president Roeland Raes sparked a media scandal by questioning the scale of the Holocaust and the authenticity of Anne Frank’s Diary. In 1992, VB introduced a controversial “70-points plan” inspired by a similar plan in France by Jean-Marie Le Pen, advocating for the mass expulsion of immigrants from Belgium as a solution to the immigration problem.

The extremism of VB motivated the other parties in parliament to systematically exclude them from power, hence the informal agreement of a “Cordon Sanitaire” in 1989. VB was disbanded in 2004 due to a court ruling that found the party sanctioning illegal discrimination. It reformed as Vlaams Belang the same year, with party leader Frank Vanhecke stating, “We change our name, but not our program.” However, the party’s popularity began to decline in the following years, reaching its lowest point in the 2014 election. This decline was widely seen as a triumph for the cordon sanitaire strategy. Nevertheless, VB soon experienced a resurgence, achieving 12 percent of the vote in 2019, matching their best election result from 2007. In late 2022, Vlaams Belang surged ahead in national polls and has maintained its position as the most popular party as of March 2024.

The VB used to be clearly right-wing on economic issues but has moved towards the centre during the last decade. It remains very critical of the EU, and has always been quite conservative on social issues. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 forced the VB to shift its position on Putin’s regime, with senior member Tom van Grieken claiming that he had been seriously mistaken about Putin and Dewinter, who earlier had praised Putin, now called him a dictator.