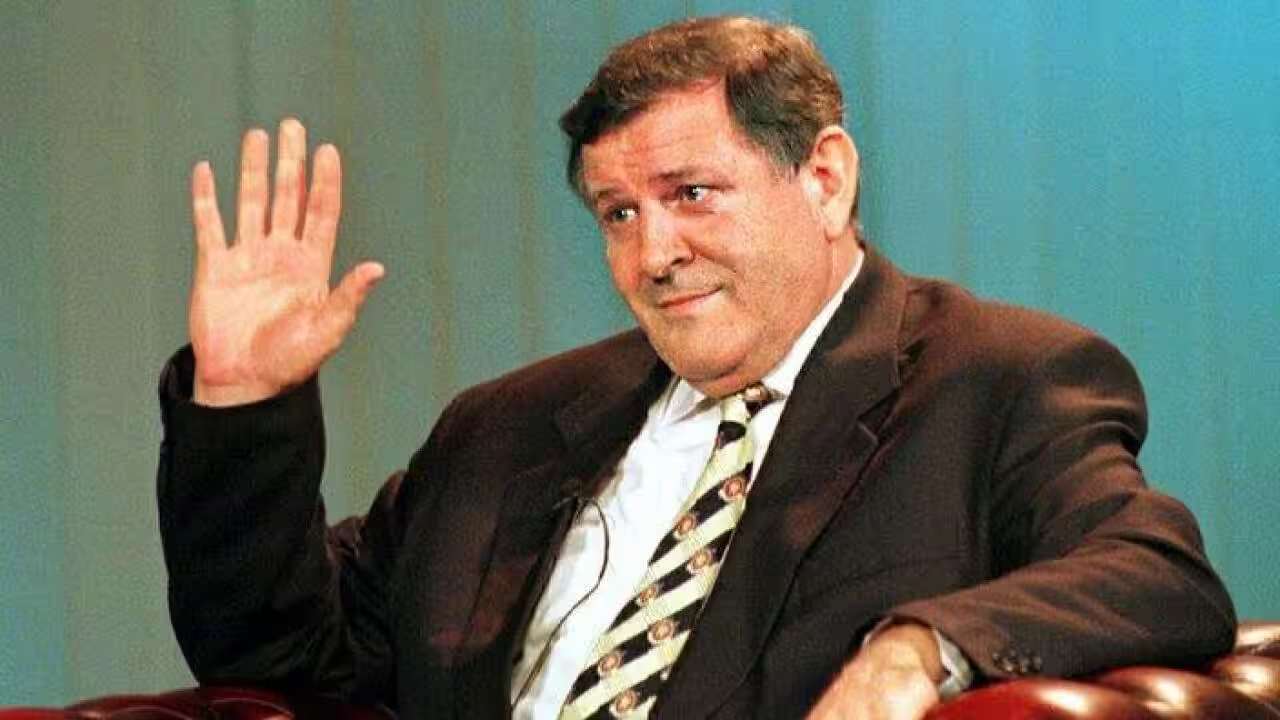

HZDS gradually lost voter support in the early 2000s. Much of their place was taken over by the left-wing populist party Smer (Direction), which was formed in 1999 by Robert Fico who had left the Party of the Democratic Left (SLD) the year before. In 2006, Smer won the election and formed a government together with HZDS and SNS, which once again worsened the country’s international relations and led to a suspension of Smer from the European Socialist Party. The government lasted for four years. After two years in opposition, Fico returned to power in 2012, now with a majority of his own. This government lasted until 2018, and then after five years in opposition, returned to power in the autumn of 2023. The formation of a government which once again led to a suspension from PES and exclusion from the S&D group in the European parliament.

In power, Smer has continued in HZDS’s authoritarian footsteps. Fico has several times described Smer as a party lacking ideology that will run the country like a business. Characteristically, “order, justice, and stability” have been highlighted as keywords in election campaigns. The party has also used nationalist rhetoric that continues along the same lines as HZDS; for example, they have described Slovakia as a nation for Slovaks, not for its minorities. The party’s roots in Slovak social democracy combined with its nationalism characterise it best as a left-wing populist and national conservative party. It is left-leaning on economic issues, conservative on social issues and has become eurosceptic in recent years, with Fico being a close ally to Hungary in Brussels.

Smer exhibits strong authoritarian tendencies, and Fico has in several ways tested the boundaries of democracy. For example, Fico’s government has proposed reforms of public broadcasting (RTVS) that have sparked sharp domestic and international criticism, where the media company would be directly subordinated to parliament and the Ministry of Culture. RTVS Director General Ľuboš Machaj said he felt reminded of the times of communist censorship. Critics of the government have also expressed concerns about threats to press freedom in the country. Fico has also attacked the Constitutional Court, and in early 2020, his government pushed through a reform that weakens the judiciary’s ability to prosecute graft, including by dismantling an anti-corruption office, in defiance of street protests across Slovakia and warnings from Brussels about safeguarding the rule of law.

Smer also has troubling Russian connections. The party has been financed by a Russian bank and has captured a significant public opinion in favour of Russia. When Fico took office as prime minister again in October 2023, the government announced that it would immediately suspend military aid to Ukraine.